Click on the above graphic to watch the video. Click in the “download” button below for the text and charts in PDF form.

The Hidden Calendar in the Gospel of John

During my roughly twenty-five years in the mainstream of evangelical Christianity I heard many times that the main distinction of the Gospel of John from the three synoptic (summary-form) Gospels was that John’s was topical while the others were chronological. However, after I discovered the Hebrew Roots Movement and Messianic Judaism, I started independently studying Scripture from the Hebrew cultural perspective of the Apostles. That opened my eyes to the powerful role of symbolism in Biblical history and prophecy, which in turn illuminated to me a hidden feast-based calendar in the Gospel of John. I now recognize that John’s “topical” Gospel is actually the most chronological of the four, and that the topics addressed in it align neatly with the nine-feast holiday cycle observed by the Hebrews at the time of Jesus’ earthly ministry.

To be clear, I am not a member of the formal Hebrew Roots Movement per se, nor of Messianic Judaism, but I am so impressed by the insights they provide to Scripture, I have designed my newly launched First Century Bible Church to be a place for mainstream Christians and Messianic Jews to interface for mutual benefit.

The secret to recognizing the hidden calendar in John is to look for the symbols associated with the seven Hebrew feasts of Leviticus 23, plus Hanukkah and Purim. Symbols and themes are frequently used in Scripture to establish context in a way that will be obvious to those with a Hebrew cultural perspective, but invisible to the uninitiated. Jesus relied heavily on this tactic to communicate with the authentic Hebrew Yahweh-worshipers in His audience through parables, which He did for the express purpose of hiding His message from others. His disciples asked “ ‘Why do You speak to the people in parables?’ He replied, ‘The knowledge of the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven has been given to you, but not to them. Whoever has will be given more, and he will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken away from him. This is why I speak to them in parables….In them the prophecy of Isaiah is fulfilled.”

That prophecy from Isaiah 6 (in context with subsequent chapters) explained that this form of hidden communication was in furtherance of God’s decision to desolate the Holy Land until the season of His second coming. Even Jesus’ explanation to the disciples about the season of restoration in Matthew 24:32-33 was hidden beneath symbolism: the fig tree, symbolic of the House of Judah (e.g. Jeremiah 24), which has been restored to the Holy Land since 1948 (or 1917 if you date her return from the Balfour Declaration).

If you start a study of John by first identifying the symbols and themes associated with the nine-feast calendar in use during Christ’s first advent, its secrets pop from the text like barley sprouts on a warm spring morning.

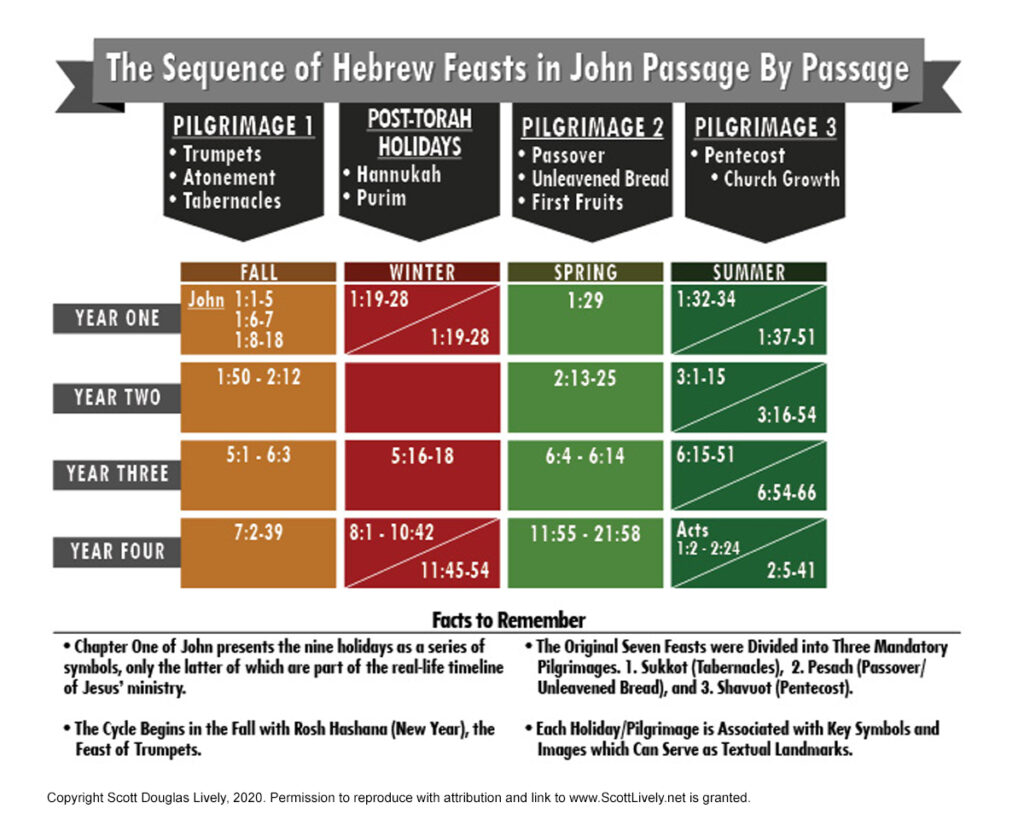

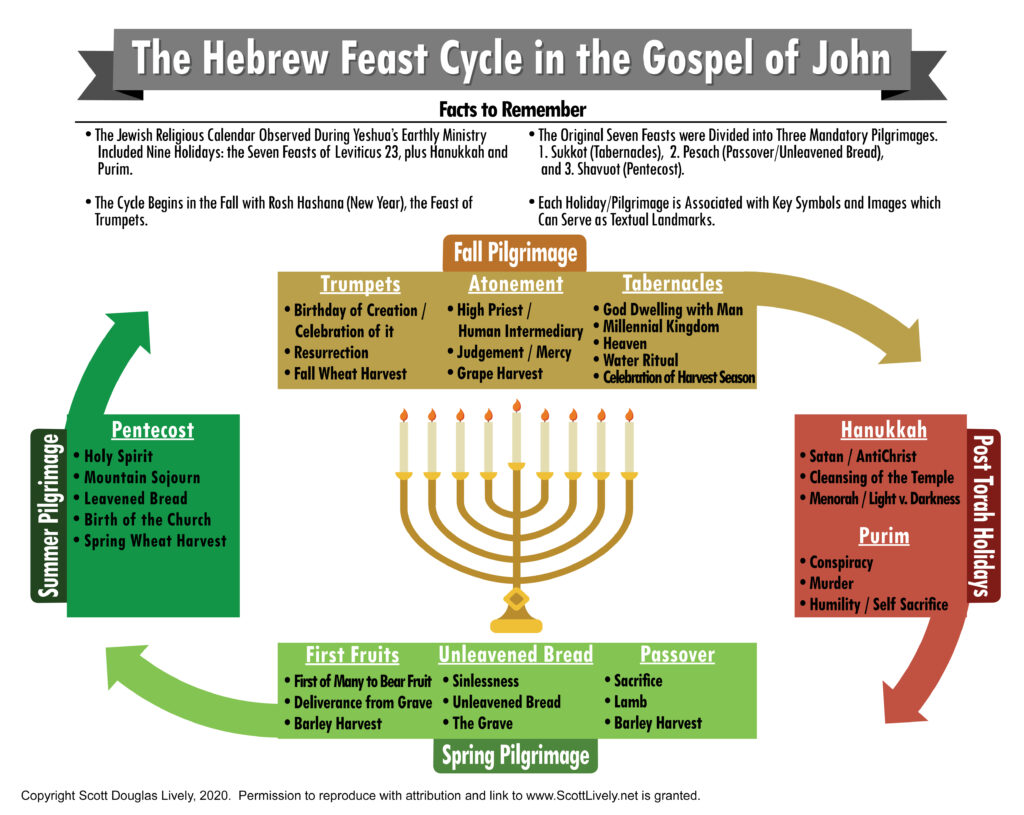

One benefit to recognizing the hidden calendar is that it proves Jesus’ ministry was 3 ½ years long, debunking a popular argument that it was a much shorter period of time. One of my charts “The Sequence of the Hebrew Feasts in John Passage by Passage” shows this graphically. Another chart “The Hebrew Feast Cycle in the Gospel of John” identifies the symbols associated with each of the nine feasts and shows how the sequence of the feasts aligns with the four seasons.

Perhaps most surprising to me in my exploration of the hidden calendar in John was the enormity of the role of Hanukkah. Hanukkah is not one of the Biblically mandated feasts of Leviticus 23, but it was designated a national holiday by the Maccabees in 165BC and is highly prophectic of the second coming of Christ when He will cleanse the Third Temple (following its defilement by the end-times Antichrist) in the same manner that the deliverer-figure “Judah the Hammer” Maccabee cleansed the Second Temple after its defilement by Antiochus IV Epiphanes (the Antichrist figure of Daniel 11).

Hanukkah is also known as the Feast of Lights and the Feast of Dedication. The theme of Jesus as “the light of the world” not only dominates the opening of the Gospel in John 1:1-14, it also dominates Chapters 8-10 which address events related to Jesus’ final Hanukkah celebration before He fulfilled the prophecy of the three Spring Feasts and Pentecost in Chapters 11-21.

Even the “topical” teachings of these three chapters prove this case. For example, John 8 opens with the story of the woman caught in adultery. Adultery is closely analogous to idolatry in the Bible (see Hosea 1-3), and the Hanukkah story heavily features Jewish idolatry fostered by Antiochus.

When Jesus forgives the adulteress, He is also symbolically offering the Jews forgiveness for their past idolatry. This would not have been lost on these Jews, for whom the Hanukkah story was as recent as the Civil War to Americans. Moreover, when “Jesus bent down and began to write on the ground with His finger,” they would have instantly connected the symbolic similarity to “drawing a line in the sand” and its unmistakable association with Antiochus (who was famously threatened with war by Rome if he “crossed the line” drawn around him in the sand without first renouncing his plan to attack Egypt.

This being so “outside the box” of common teaching, some may balk at this interpretation, but immediately following that account, Jesus declares in John 8:12 “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows Me will never walk in the darkness, but will have the light of life,” followed by several additional topical clues. And John 10:22 states specifically “At that time the Feast of Dedication took place in Jerusalem,” a closing bookend confirming the three-chapter Hanukkah theme.

To be sure, studying symbols and themes can be like following a cryptic treasure map compared to the (fully valid) plain surface meaning of the text, but the diligence it requires is a trait God loves to see us develop.